Stakeholders in Nigeria’s disability and development ecosystem have renewed calls for a decisive shift in disability inclusion—from symbolic compliance and token representation to genuine influence, leadership, and participation in decision-making processes.

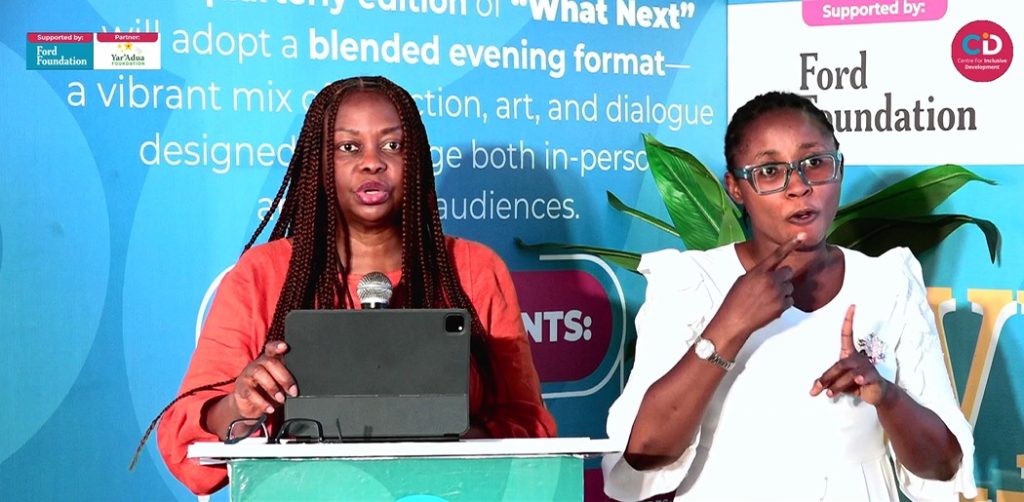

This call resonated strongly at a stakeholder engagement convened by the Centre for Inclusive Development (CID), which brought together disability rights advocates, gender justice leaders, civil society actors, private sector representatives, funders, and researchers to critically interrogate prevailing inclusion practices and reimagine more transformative approaches.

The engagement marked the inaugural edition of “What Next – An Evening of Intersectional Conversations,” a cross-movement dialogue designed to explore how lessons from the gender justice movement can strengthen disability advocacy and accelerate structural change.

For participants, the central question was clear: Why does disability inclusion in Nigeria often stop at visibility without translating into power, accountability, and justice?

Evidence as a Tool for Change

A major highlight of the event was the presentation of CID’s research on gender-based violence (GBV) against women with disabilities in Nigeria, which provided rare and much-needed evidence on the intersecting forms of violence and exclusion faced by women with disabilities.

The findings reinforced the urgent need for disability-responsive GBV prevention and response systems, while also underscoring the importance of data and lived experience in shaping policy, funding priorities, and advocacy strategies.

“Inclusion Without Power Is an Illusion”

Delivering the keynote address, Dr. ChiChi Aniagolu-Okoye, Regional Director for West Africa at the Ford Foundation, offered a piercing critique of dominant disability inclusion narratives in Nigeria.

“Check-boxing inclusion gives visibility without power, presence without influence, and acknowledgement without justice,” she said.

Dr. Aniagolu-Okoye emphasized that disability inclusion must be understood as a structural and political issue, deeply embedded in systems of power, governance, policy design, and social norms—rather than a procedural obligation satisfied by quotas or representation.

She highlighted intersectionality as a critical framework, noting that women and girls with disabilities experience layered forms of exclusion that cannot be addressed through isolated or single-issue interventions.

“A woman with a disability is not simply a woman and a disabled person. Multiple, intersecting forms of discrimination shape her experiences,” she stated.

Drawing from decades of feminist organizing, Dr. Aniagolu-Okoye identified strategic shifts relevant to disability advocacy, including moving from stand-alone disability projects to mainstreaming inclusion across institutions, centering lived experience as legitimate expertise, and using research and evidence to influence policy and funding decisions.

“Inclusion is not about being invited into the room,” she concluded. “It is about having the power to shape decisions.”

Movement Building Beyond Charity

A panel discussion moderated by Rasak Adekoya further unpacked these themes, featuring Hajiya Saudatu Mahdi of the Women’s Rights Advancement and Protection Alternative (WRAPA), Esther Akinnukawe of MTN Nigeria, and Ene Obi, human rights activist and former Country Director of ActionAid Nigeria.

Mahdi drew on feminist movement-building principles, stressing the need to frame disability not as a welfare concern but as a political constituency with collective power.

“Disability should be seen as a constituency, not just a label,” she said, noting that such framing shifts engagement away from charity and toward rights, accountability, and political action.

Reflecting on the women’s movement, Mahdi observed that progress became possible when women across diverse identities recognized themselves as part of a shared struggle.

“Movement building starts with belonging—knowing who we are and how we want to be seen,” she added.

Lessons from the Private Sector

From a corporate perspective, Akinnukawe drew parallels between early gender inclusion efforts in Nigerian workplaces and the current state of disability inclusion.

“When gender inclusion began, it was largely driven by compliance, and that was necessary at the time,” she said. “But once women entered professional and leadership spaces, they demonstrated value, and organizations began to see the business case.”

She suggested that disability inclusion could follow a similar trajectory if organizations move beyond surface-level adjustments to intentional access, opportunity, and leadership pathways.

Accountability Beyond Laws

Ene Obi focused her intervention on accountability and the disconnect between laws, institutions, and lived realities.

“Having a law or a commission is not the same as using it,” she said. “The real question is how these frameworks are held accountable.”

Obi cautioned against isolating disability advocacy from broader struggles for social justice, arguing that fragmentation weakens political influence. She also emphasized the importance of leadership expansion within movements.

“One person cannot make a movement,” she said, calling for deliberate leadership development, internal accountability, and collective ownership of advocacy goals.

From Symbolic Inclusion to Structural Power

The event, facilitated by Esther Hadiza Ihejeaku, spotlighted a persistent challenge within Nigeria’s civic and development landscape—where disability inclusion is frequently treated as a compliance obligation rather than a rights-based and structural imperative.

CID noted that the What Next series was intentionally created to foster cross-movement learning, elevate lived experience and evidence, and generate insights capable of influencing policy, programming, and partnerships.

Across discussions, participants agreed that disability inclusion must move decisively from symbolism to influence, leadership, and decision-making power, with intersectionality serving as a critical lens—particularly in addressing the compounded exclusion faced by women with disabilities.

The presentation of CID’s GBV research anchored the conversations in evidence, reinforcing a core message echoed throughout the evening: without data, lived experience, and accountability, inclusion remains performative rather than transformative.

Click the link below to join our WhatsApp channel