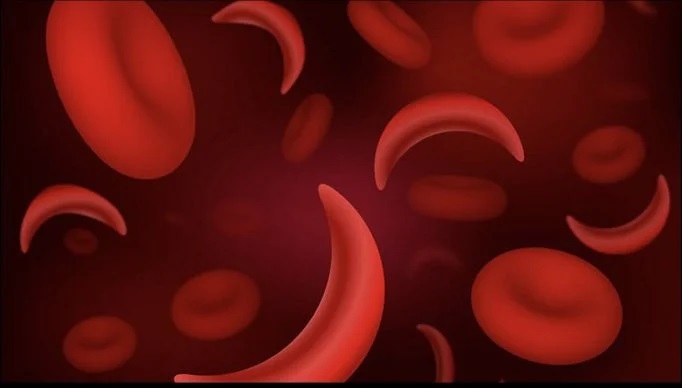

People with sickle cell disease live with ‘disabilities’; let’s accept that first. An estimated four million people in Nigeria live with sickle cell disease (SCD), a genetic blood disorder with no imminent feasible cure. Yet, just because there is no feasible cure for sickle cell disease does not mean that people living with it cannot enjoy most of the activities other people do. They can if they have the correct information, assistance and support.

So why are so many Nigerians suffering silently and dying of this manageable disease? There are two primary reasons: lack of socio-economic support and poor access to early-onset medical care.

We can start to improve the lives of Nigerians with sickle cell by lifting the taboo over the term “disability.” If we classify this disease as a disability – as many developed nations already do – people with the blood disorder could access State-established social protection programmes, disability-inclusive employment, and subsidised health financing with the National Health Insurance Scheme through the Physically Challenged Persons Social Health Insurance Programme (PCPSHIP).

Increasing access to these programmes can improve and save lives. The World Health Organisation has recently estimated that 70% of sickle cell-related deaths and complications are preventable through cost-effective interventions that include comprehensive health and mental care.

So why are people living with sickle cell resisting this categorisation?

Nigerians’ bias against people with disabilities is holding back the sickle cell community. By shifting our perception of the term, we can have a positive impact on the more than 4 million Nigerians living with the disease. Since Nigeria ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities in 2007, it has taken 12 years for the nation to sign the Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act 2019. In the meantime, disabled groups are bullied, stigmatised and excluded.

In recent conversations with different sickle cell disease support group, I learned that the term “disability” was automatically viewed as offensive not because they thought it was but rather because of the bias associated with the word in our community. This is one of the major reasons the sickle cell disease community does not want to be included in the disability inclusion framework. Further conversation highlighted that because of this perception, they have not been sensitised to the actual benefits.